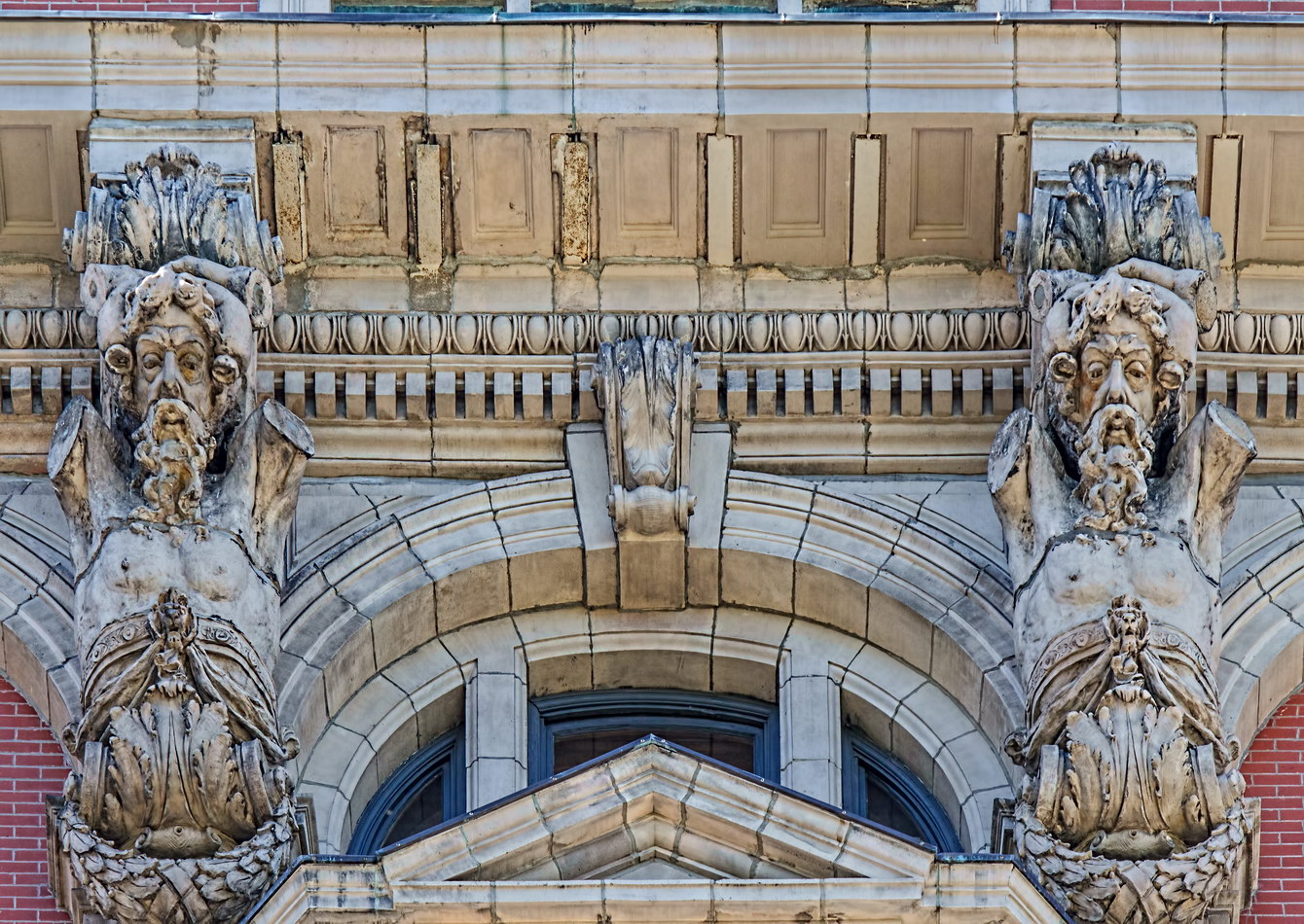

Alwyn Court Apartments is undoubtedly the most decorated building in New York: Gray terra cotta covers every foot of the 12-story building. When the building opened in 1909 it was as opulent inside as it is outside. Each apartment (two to a floor) had 14 rooms and five baths – except for the 32-room apartment!

The building had a stroke of bad luck just months after opening, when only five apartments were occupied – a fire damaged some of the upper floors. The building was repaired and filled quickly, but dropped out of fashion in the late 1930s. And the Great Depression didn’t help. The bank foreclosed and reconfigured Alwyn Court as 75 much smaller apartments under direction of architect Louis H. Weeks. The main entrance on the corner was converted to retail space (now the Petrossian restaurant); the former service entrance on Seventh Avenue is now the main entrance.

As part of a co-op conversion, the building’s facade was cleaned and restored in 1980 by Beyer Blinder Belle, an architectural firm specializing in historic preservation.

The fire-breathing dragons at the corner entry (and elsewhere) are actually salamanders; a crowned salamander was the emblem of Francis I, King of France. (The same emblem graces Red House, another apartment building designed by Harde & Short.)

Alwyn Court Vital Statistics

- Location: 180 W 58th Street at Seventh Avenue

- Year completed: 1909

- Architect: Harde & Short

- Floors: 12

- Style: French Renaissance

- New York City Landmark: 1966

- National Register of Historic Places: 1979

Alwyn Court Recommended Reading

- Wikipedia entry

- NYC Landmarks Preservation Commission designation report

- The New York Time column

- Daytonian in Manhattan blog

- City Realty review

- James Maher Photography blog

- Mindful Walker blog