336 Central Park West is a modest Art Deco apartment building that you might pass without thought – unless you looked up. The undulating, gently flared cornices on the building and its tower enclosures are embossed in an Egyptian reed pattern that is both simple and stunning.

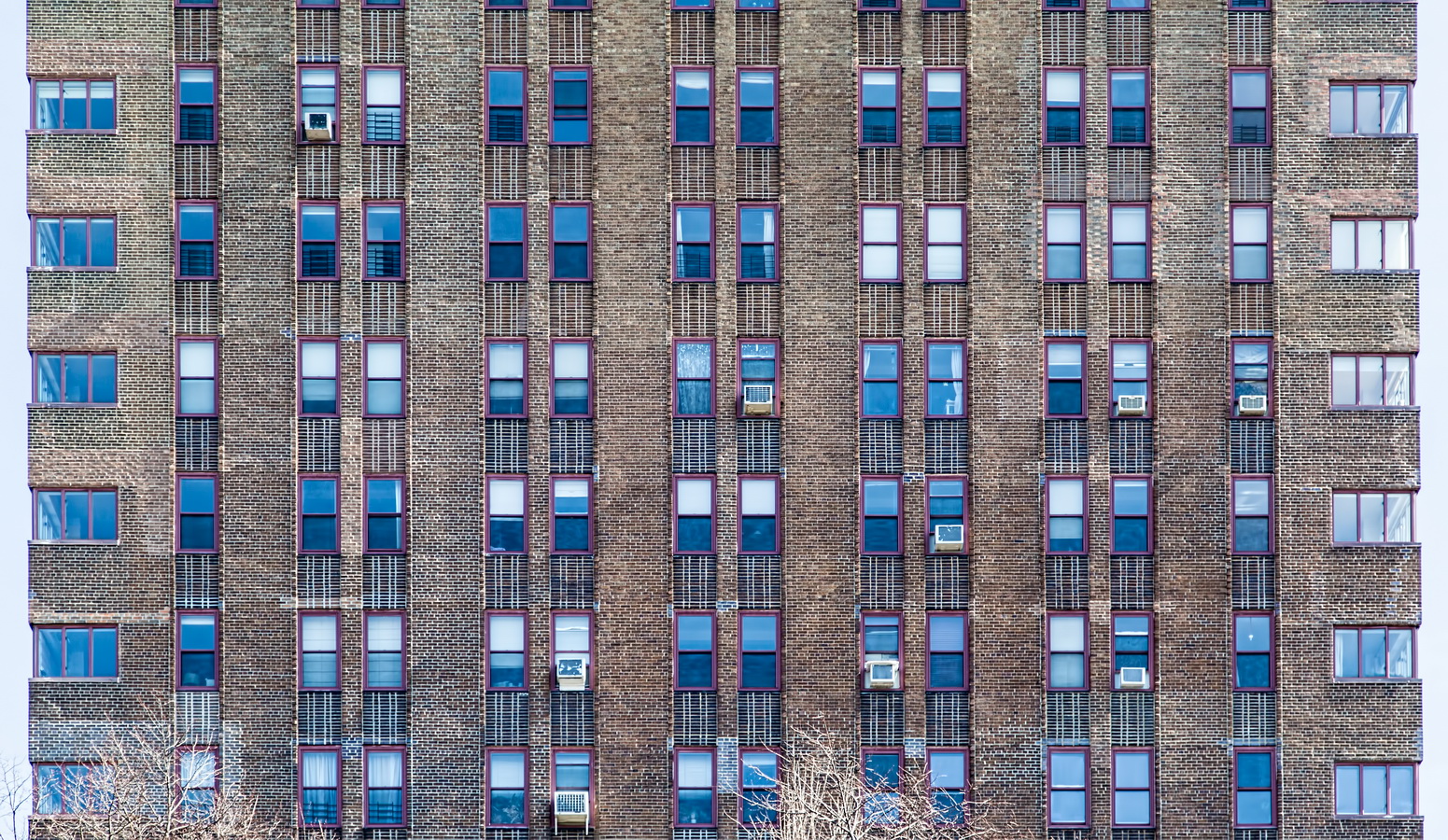

You might also notice the thoughtful polychrome brickwork, with its projecting piers and segmented spandrels, which emphasize the building’s height.

Alas, over the years the cooperative has spoiled the design and created a stew of replacement windows – casements, double-hung, sliders in a variety of single and multi-pane configurations. Through-wall air conditioning vents are also done in different styles. Even the ground floor doors are mismatched.

336 Central Park West Vital Statistics

- Location: 336 Central Park West at W 94th Street

- Year completed: 1930

- Architect: Schwartz & Gross

- Floors: 16

- Style: Art Deco

- New York City Landmark: 1990

336 Central Park West Recommended Reading

- Wikipedia entry (Schwartz & Gross)

- NYC Landmarks Preservation Commission designation report (Upper West Side/Central Park West Historic District – pg. 54)

- City Realty review

- Columbia University Libraries Real Estate Brochure Collection

- Prewar Passion: Schwartz & Gross

- Emporis database