Goelet Building * looks surprisingly modern for architecture more than a century old. The structure was built in two stages. The first five floors were completed in 1887. The original sixth floor was demolished in 1906† and replaced with five floors that more or less mimicked the three floors below.

The Maynicke & Franke addition blends very well with the McKim, Mead & White original. The NYC Landmarks Preservation Commission notes minor differences in materials and patterns, but the final result maintains a colorful, yet elegant appearance. This is no small accomplishment; add-on floors can be disastrous. Just take a look at De Lemos & Cordes’ 1889 Armeny Building, defaced by a two-story addition in 1893.

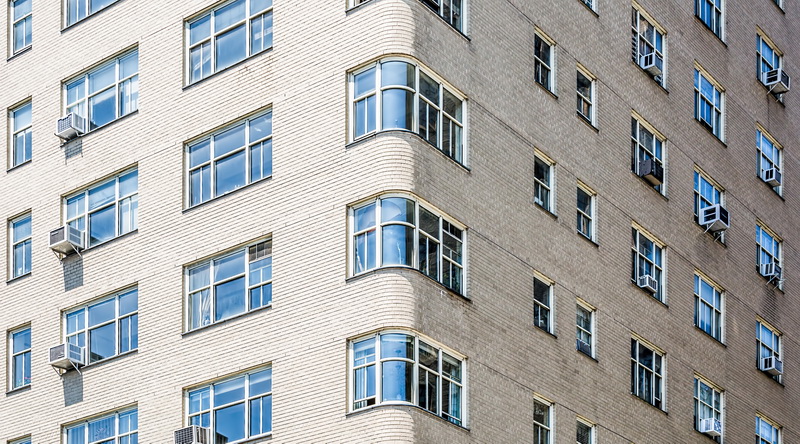

As with their Warren Building diagonally across the street, McKim, Mead & White faced the challenge of a non-rectangular plot. They rounded the corner, to avoid the awkward corner dictated by the property line.

In his New York Times Streetscapes column, historian Christopher Gray lauds the Justin family for rescuing the Goetlet Building from decline. Zoltan Justin bought the building in 1977. He and son Jeffrey cleaned the facade, removed non-historic elements, and restored the structure to its original glory.

* Not to be confused with the 1932 Goelet Building, now known as Swiss Center Building, located at Fifth Avenue and W 49th Street.

†See Tom Miller’s post in Daytonian in Manhattan for a look at the original six-story building.

Goelet Building Vital Statistics

- Location: 900 Broadway at E 20th Street

- Year completed: 1887; enlarged in 1906

- Architect: McKim, Mead & White; 1906 expansion by Maynicke & Franke

- Floors: 10

- Style: Industrial

- New York City Landmark: 1989

Goelet Building Recommended Reading

Google Map