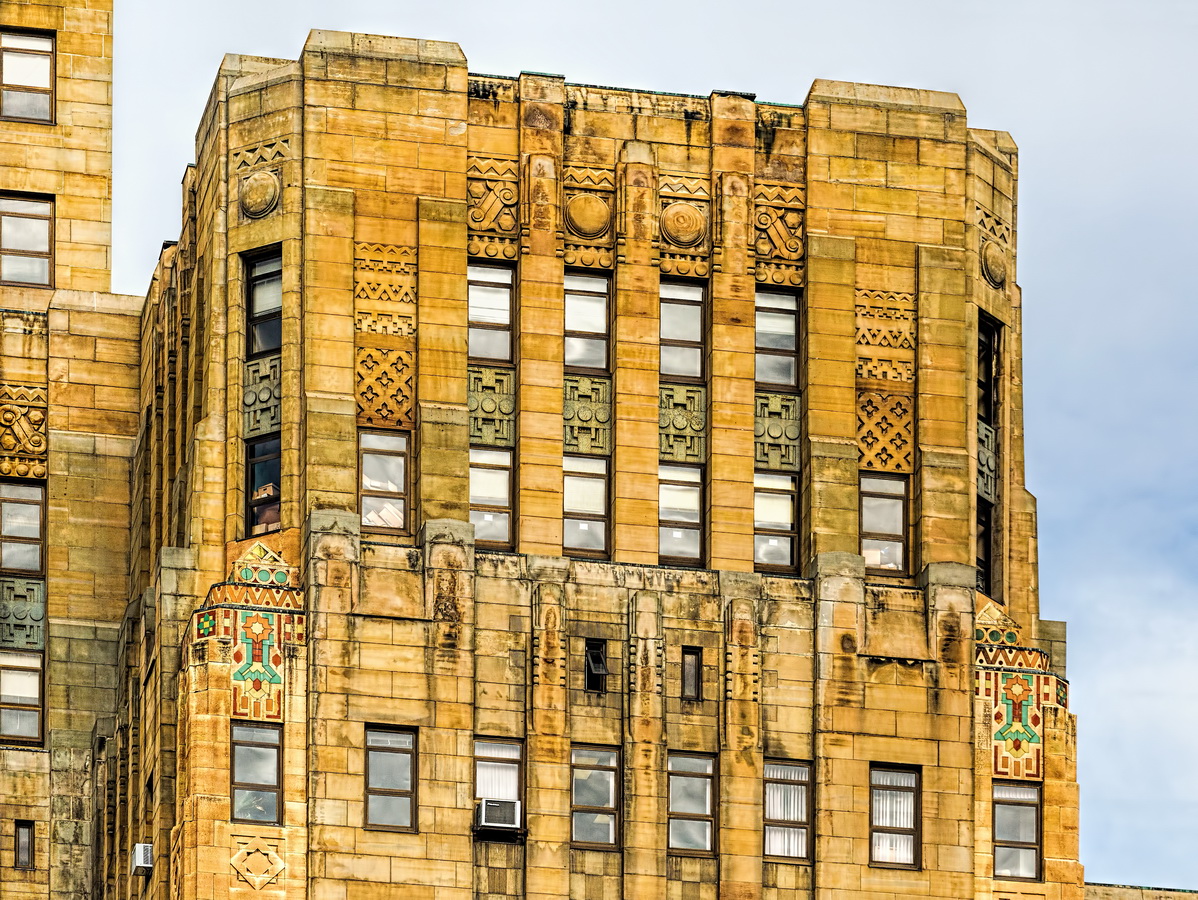

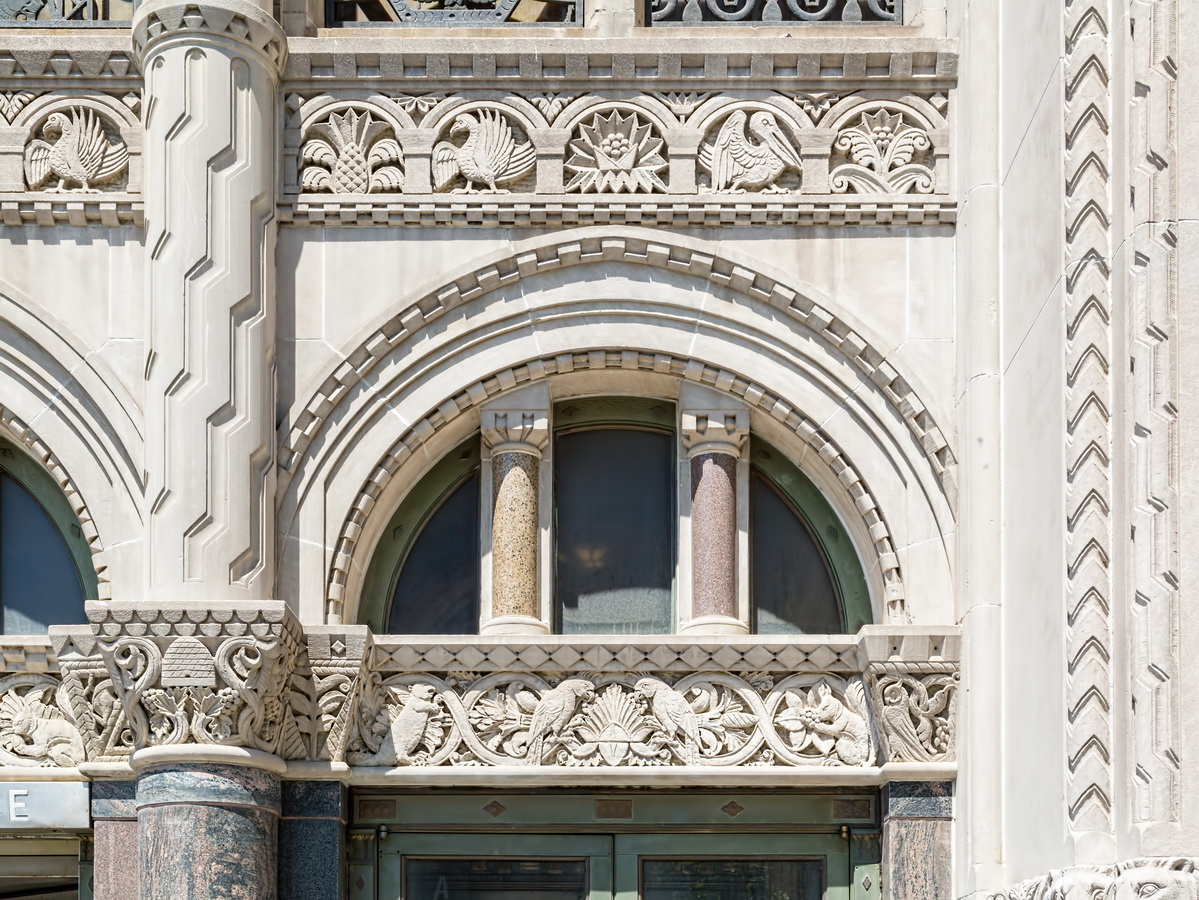

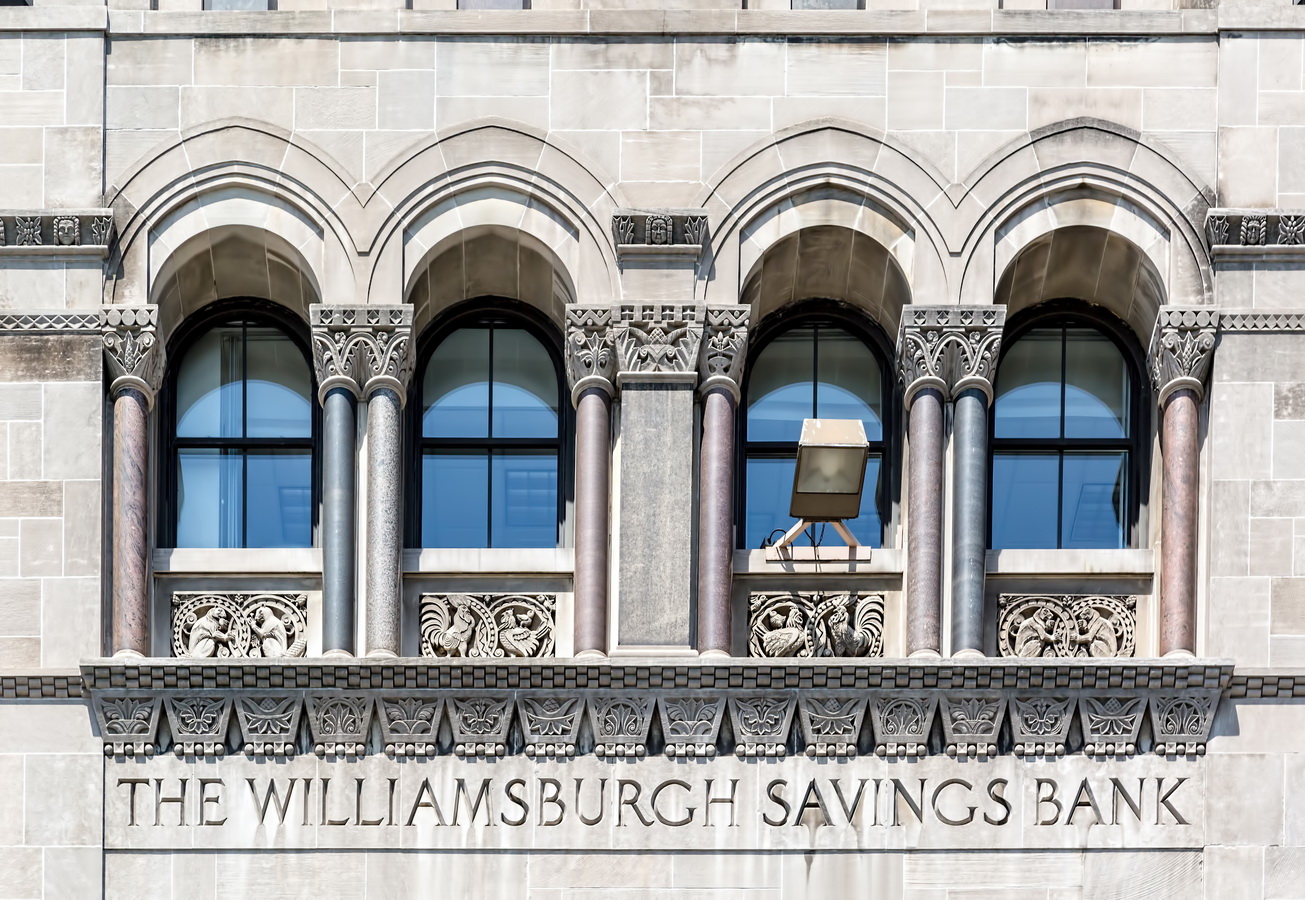

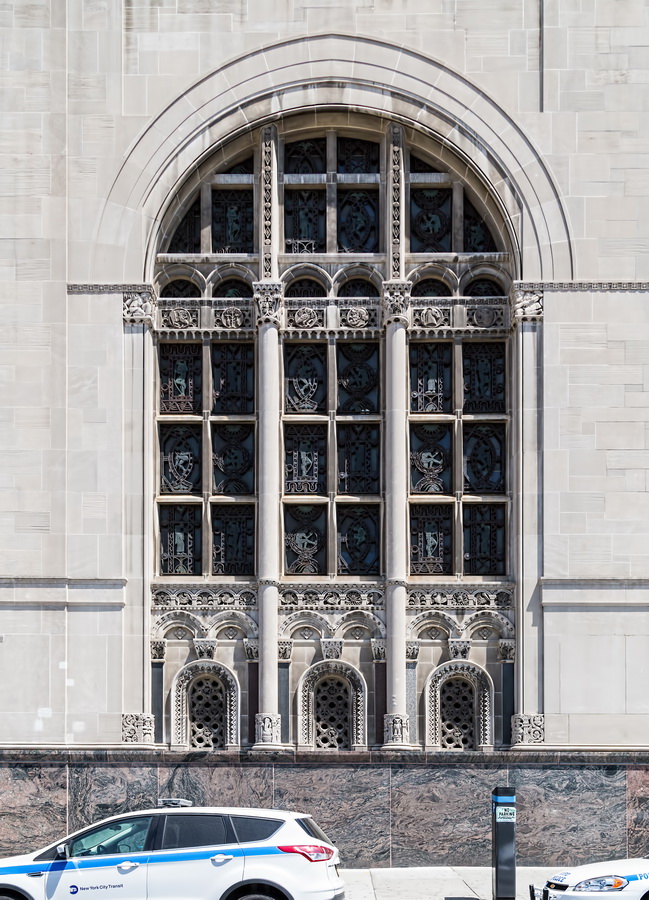

Buffalo City Hall is the city’s most dramatic building. When built, it was among the largest, tallest and most expensive city halls in the country. But it’s the style and ornamentation that makes this structure so impressive.

From the richly carved granite base to the illuminated polychrome terra cotta crown, the soaring tower of limestone and sandstone is finely detailed to accentuate the skyscraper’s height and Buffalo’s place in history.

City fathers enlisted the talents of skilled artisans: Albert T. Stewart for the portico frieze; William de Leftwich Dodge for the lobby murals; René Chambellan for detail sculpture; Bryant Baker for bronze statues of Presidents Millard Fillmore and Grover Cleveland; ceiling vault by Rafael Guastavino.

Beyond Buffalo City Hall’s artistic merits, the landmark has some notable architectural features. Instead of merely cloning each floor, plans were customized to meet the needs of the city departments that were to occupy the spaces. All of the building’s 1,520 windows open inward, so they can be washed from the inside. Offices were originally cooled by a “green” wind-powered ventilation system: Large vents in the western facade channeled strong winds off Lake Erie through cool subterranean chambers and then back through the building.

Local lore pokes Buffalo politicians. Architect John Wade designed the Common Council Chamber with pillars, each to hold busts of famous Buffalonians. But Council members could not agree who was to be honored. Plan B emerged, to have each pillar display the virtues – such as Fidelity, Prudence, and Faithfulness – of Councilmen. Ever since, the public has asked why Honesty, Efficiency and Economy are missing.

Although City Hall is no longer Buffalo’s tallest building – it was overtaken by One Seneca Tower in 1970 – the 28th floor observation deck is still a favorite tourist stop. The city provides free tours of the building, daily at noon.

Buffalo City Hall Vital Statistics

- Location: 65 Niagara Square

- Year completed: 1931

- Architect: George J Dietel and John J Wade

- Floors: 32

- Style: Art Deco

- Buffalo City Landmark

- National Register of Historic Places: 1999

Buffalo City Hall Recommended Reading

- Wikipedia entry

- City of Buffalo: City Hall History

- Buffalo’s Best article

- Preservation Buffalo Niagara listing

- Emporis database

- Buffalo City Hall: Americanesque Masterpiece by John H. Conlin

- Buffalo Architecture: A Guide