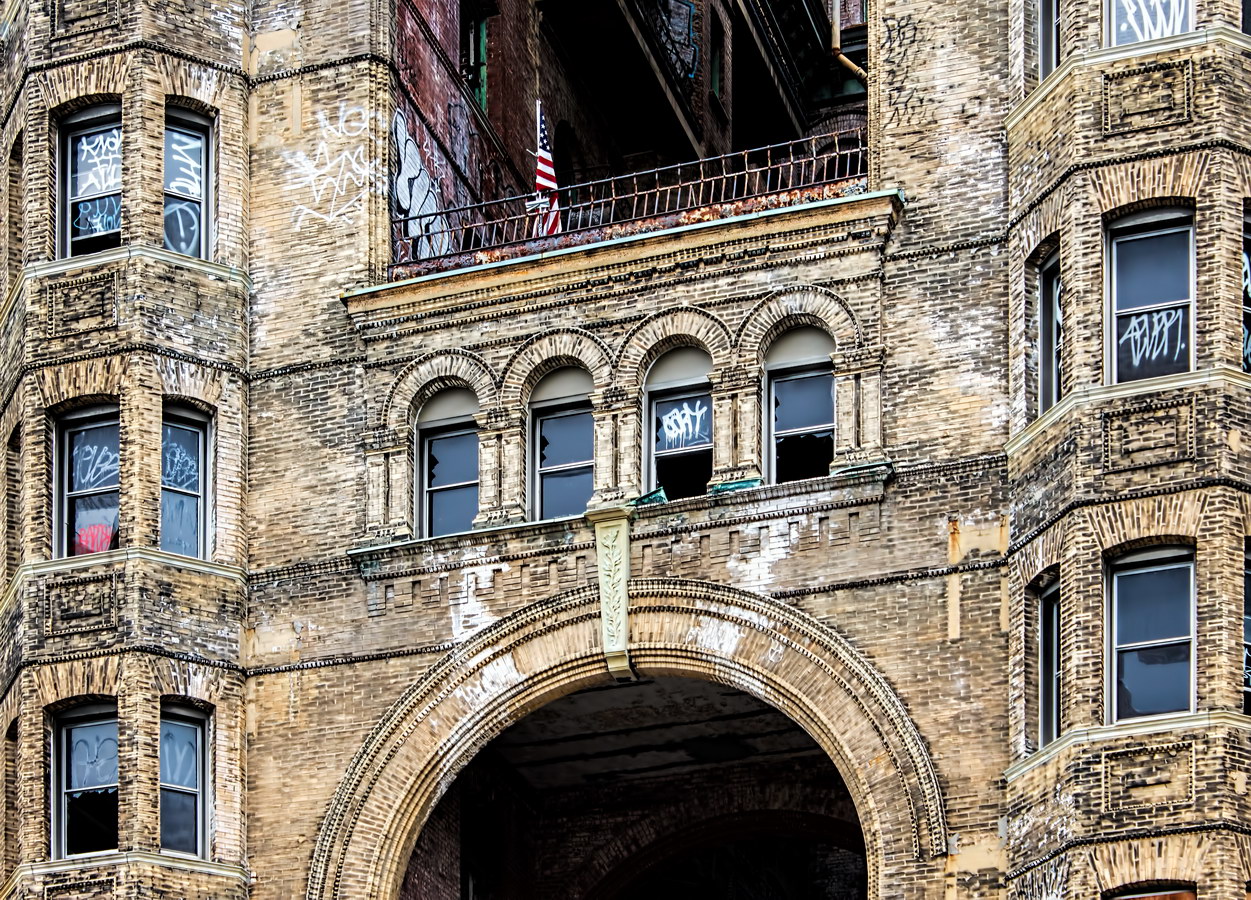

The Madison Belmont Building was a prominent addition to the young “Silk District,” commercial buildings serving the silk industry that replaced the mansions of uptown-bound wealthy New Yorkers. It was among the first in the U.S. to use Art Deco design elements, according to the NYC Landmarks Preservation Commission. The overall design, however, was traditional. Like other tall buildings of the time, the Madison Belmont Building had a base – shaft – capital organization mimicking a classical column.

Although architect Whitney Warren had been exposed to Art Deco concepts while in Paris, it appears that prime tenant Cheney Silk Company also influenced the design. The company had a relationship with Edgar Brandt, a pioneer of the Art Deco style in Paris. Warren picked Brandt to design the iron and bronze framing around the showroom windows of the lower three floors, as well as the entrance doors and grilles.

The white 18th floor was added in 1953 – 29 years after the original construction.

Despite the Madison Belmont Building’s pioneering role, architects Warren & Wetmore are better known for their neo-Renaissance and Beaux Arts works, such as the New York Yacht Club, Grand Central Terminal, New York Central Building (aka Helmsley Building), Steinway Hall, Aeolian, and Heckscher Building (aka Crown Building).

Madison Belmont Building Vital Statistics

- Location: 181 Madison Avenue at E 34th Street

- Year completed: 1925

- Architect: Warren & Wetmore

- Floors: 18

- Style: neo-Renaissance, with Art Deco decoration

- New York City Landmark: 2011

Madison Belmont Building Recommended Reading

- Wikipedia entry (Warren & Wetmore)

- NYC Landmarks Preservation Commission designation report (exterior)

- NYC Landmarks Preservation Commission designation report (interior)

- The New York Times Streetscapes column

- Emporis database