Citigroup Center is remarkable New York architecture, with an engineering story even more dramatic than its photographs. The distinctive floating tower (renamed 601 Lexington Avenue in 2009) became a scary 59-story lesson for architects, engineers, public officials, lawyers and journalists worldwide.

Two elements make Citigroup (originally Citicorp) Center so distinctive: The southwest-facing 45-degree roof and the nine-story stilt base.

The signature angled roof, unmistakably visible for miles, was designed as a solar collector. A power gauge in the lobby once showed how much electricity was being generated by the sun. Apparently the solar panels were no threat to Con Ed – they’ve since been unplugged.

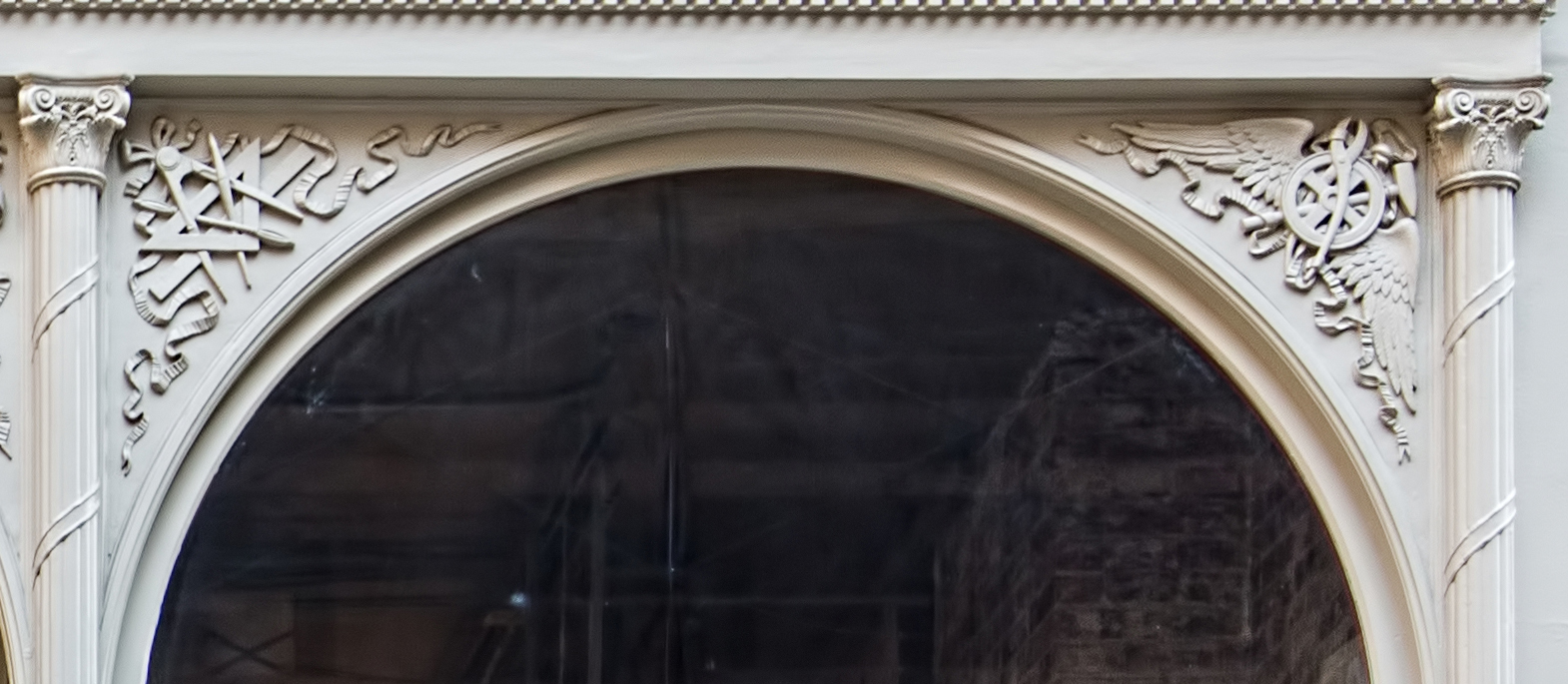

The stilt base was designed to turn a profit, not heads. It was almost a disaster.

The nucleus of the building’s site was owned by St. Peter’s Lutheran Church, which wanted to sell the land and use the profits to build a new church in a less valuable location. As Citicorp assembled the other pieces of the site, St. Peter’s discovered that they couldn’t locate a suitable new church site. Oops. Citicorp’s solution was to build a new church on the corner, and erect the office tower above the church. (See “Holdouts!: The Buildings That Got in the Way ” by Andrew Alpern and Seymour Durst for the full story.)

” by Andrew Alpern and Seymour Durst for the full story.)

With the church located on the corner, the tower supports had to be placed at the center of each wall, instead of at the corners. This, in turn, required special bracing to transfer the weight of the building to the piers.

There was a miscalculation. In determining the maximum loads, LeMessurier had considered the effect of winds perpendicular to the facades – but not “quartering” winds that would push against two sides simultaneously. Making matters worse, the steel contractor had substituted bolted joints for the much stronger (but $250,000 more expensive) welded joints that were specified. LeMessurier discovered the error and the bolt substitution a year after the building was completed. The engineer ordered wind tunnel tests and discovered to his horror that the building was vulnerable to winds over 70 m.p.h.

After urgent meetings with Citicorp, LeMessurier ordered two-inch-thick plates to be welded in place over the bolted joints. Welders worked every night for three months in a race against hurricane season. They almost lost: Hurricane Ella was headed for New York on Sept. 1, 1978 but fortunately it turned out to sea, averting a massive evacuation of the neighborhood. (The Red Cross had estimated 200,000 deaths if the building toppled.)

The massive repair project went virtually unreported for 17 years – a newspaper strike hit New York just as the repairs began; The New Yorker broke the story in 1995. Diane Hartley, a Princeton engineering student, was the hero in this drama. In the course of writing her thesis, she had questioned LeMessurier’s calculations – triggering his reevaluation of the design. LeMessurier’s unflinching disclosure of the problem is today used as a case study in professional ethics.

In 2002 the building was reinforced again – this time one of the massive base columns was encased in steel and copper to protect against a terrorist bomb blast.

The engineering crisis overshadowed Citicorp Center’s other impressive features: Double-decker elevators used interior space more efficiently; a tiered, sunken plaza beneath the building’s southwest corner provides space for sidewalk cafes and entry to the subway system; a 410-ton “tuned damper” system in the crown minimizes the building’s wind-induced swaying.

Drama notwithstanding, Citigroup Center is an impressive and attractive addition to New York’s architectural treasure chest, whether viewed from afar, up close or inside.

Citigroup Center Vital Statistics

- Location: 601 Lexington Avenue between E 53rd and E 54th Streets

- Year completed: 1977

- Architect: Hugh Stubbins, Jr.

- Structural Engineer: William LeMessurier

- Floors: 59

- Style: Postmodern

Citigroup Center Recommended Reading

- Wikipedia entry

- The New Yorker: THE FIFTY-NINE-STORY CRISIS (May 29, 1995)

- The American Institute of Architects LeMessurier Stands Tall: A Case Study in Professional Ethics

- The New York Times William LeMessurier, 81, Structural Engineer, Dies (June 21, 2007)

- The New York Times Hugh Stubbins Jr., 94, Creator of Emblematic Skyscrapers, Is Dead (July 11, 2006)

- The New York Times A Midtown Skyscraper Quietly Adds Armor (August 15, 2002)

- Emporis database

- PBS Wonders of the World

- New York City: Privately owned Public Space

- The City Review blog

- The New York Times F.Y.I. (Citigroup Center’s tuned damper anti-sway mechanism) (February 2, 1997)

- The New York Times ARCHITECTURE VIEW; AFTER OPULENCE, A NEW ‘LITE’ ARCHITECTURE (May 20, 1990)

- Great Buildings listing

- “Holdouts!: The Buildings That Got in the Way

” by Andrew Alpern and Seymour Durst

” by Andrew Alpern and Seymour Durst

Google Map