Columbus Circle and vicinity has been through a major building boom in recent years, so glass and steel are pushing aside stone and terra cotta; enjoy the classics while they last!

Columbus Circle and vicinity has been through a major building boom in recent years, so glass and steel are pushing aside stone and terra cotta; enjoy the classics while they last!

Crossroads of the world, heart of the city that never sleeps – the only place where there are crowds on a cold Sunday afternoon. And the only place where bright lights are part of the zoning regulations: You have to have a big electric display on your facade.

Bit by bit, the stately old-guard stone and terra cotta buildings of the early 1900s are being replaced by glass and steel towers, some with bizarre shapes and colors. The building that pretty much started it all – One Times Square, the one-time headquarters of The New York Times – is still there, but hardly in its 1905 form. Allied Chemical covered it in white marble in 1964, and it has since become a 25-story electric signboard. The Paramount Building also survives, along with some theater buildings between Seventh and Eighth Avenues and Bush Tower between Broadway and Sixth Avenue (Avenue of the Americas). Up and down the uptown side streets (43rd – 47th) are plenty of landmark-quality buildings, though – and not just theaters.

You’ll find several distinctive old clubs in the area, and the art deco treasure McGraw-Hill Building and the Port Authority Bus Terminal. You’re also just a hop, skip and a jump from Bryant Park and the main branch of the New York Public Library.

Whether brick is used as a load-bearing structural element or merely as a decorative/protective veneer, New York architects have many creative ways to alter the appearance of a brick façade. Designers can select different types, colors, textures and sizes – and then specify different patterns for laying the courses.

Types: Common brick and facing brick are the main types; facing brick has been manufactured for its aesthetic qualities – color and surface texture. Facing brick is further typed by degree of uniformity in color and lack of chips, cracks, etc. (We’re ignoring other special types such as firebrick that don’t contribute to a building’s overall appearance.)

Colors: Bricks (and the mortar holding them together) can be ordered in hundreds of different colors. Architects can mix colors – either randomly or in distinct patterns – to create different visual textures. (The use of several colors in architecture is called “polychrome.”)

Textures: The manufacturing method and clay type determine a brick’s surface texture, which could be rough, smooth or even shiny (glazed). In addition, bricks can be given a patterned surface (like the milled edge of a quarter).

Nominal sizes: The modular brick is just one of three named sizes that are 2-2/3 inches thick (three courses = 8 inches); Norman brick is 4 x 2-2/3 x 12 inches, SCR brick is 6 x 2-2/3 x 12 inches. Two sizes are 3-1/5 inches thick (5 courses = 16 inches); engineered brick is 4 x 3-1/5 x 8 inches, Norwegian brick is 4 x 3-1/5 x 12 inches. Roman brick is 4 x 2 x 12 inches (4 courses = 8 inches). Economy* brick is 4 x 4 x 8 inches (2 courses = 8 inches). Nominal size is slightly larger than the brick’s actual physical size, to allow for the thickness of the mortar joint. Because the mortar joints are a uniform thickness, brick size affects the mortar/brick ratio – and thus, appearance.

* “Economy” because it takes less mortar and labor to use thicker bricks: For a 10-foot-tall wall, modular brick requires 45 courses, economy brick needs only 30 courses.

Orientation: There are six basic ways to lay a brick. Viewed from the face of the wall, a brick laid:

And just to make things more interesting, bricks can be corbelled (projected from the wall surface) or angled (to give a toothed appearance) or gauged (shaped) to a non-rectangular profile, as in an arch.

Bond: The overlap pattern adds another element of variety. The most common pattern is running bond or stretcher bond – stretchers that overlap the course below by half. Add a course of headers after every five or six courses of stretchers and you get American bond. Alternating courses of headers and stretchers are called English bond. Alternating headers and stretchers in the same course (with headers centered on stretchers above and below) are called Flemish bond. Other bonds have more complex patterns, often accentuated by contrasting-colored bricks or by corbelling.

Architects’ artistic preferences, alas, may be shackled by accountants: Thinner bricks require more mortar and labor per foot of elevation than thick bricks; complex patterns likewise take more labor (and may take more bricks) than simple common bond or American bond.

Amazon.com has more than a thousand book titles dealing with New York City architecture, so there’s no shortage of reading material on this subject! I’ve spent a fair amount of time (and money) browsing physical and online book stores – here’s a short list of architecture books that I’ve found particularly helpful and enjoyable.

I’ve categorized the books by scope: Some are about Architecture in New York City; others are about Architecture in general; yet others are about New York City. I think you’ll find all to be interesting and useful.

Just click on the titles to see these books in Amazon.com (As an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases)

Norval White and Elliot Willensky with Fran Leadon | 1055 pages | Oxford University Press | 2010

If you find that the architecture bug has bitten you – beware, there is no antidote – you will need a guide. The best guide, IMHO, is “AIA Guide to New York City.” The fifth edition includes 955 pages of maps, photos and detailed block-by-block, building-by-building commentary on virtually every architecturally significant structure within the five boroughs – even noting significant demolitions! The AIA Guide has nearly 100 pages of subject and address indexes, a glossary of architectural terms, even touring and photography tips. You can use the book as a walking tour guide, as a reference book, or as a history book of sorts (read about real estate development battles, zoning law trades, etc.). The authors’ scholarship is matched by their wit, so you’ll be entertained as well as educated. The “AIA” in the title, by the way, stands for American Institute of Architects.

Dirk Stichweh, photos by Jörg Machirus and Scott Murphy | 192 pages | Prestel | 2016

This is a magnificent celebration of the buildings that make New York’s skyline so exciting. The large 9½ʺ x 12½ʺ format and brilliant color photography make “NY Skyscrapers” a joy to browse again and again. You’ll find the city’s classic icons, of course, but also less-photographed and under-appreciated structures such as the West Street Building, Crown Building, and Paramount Building. Half of the photos are high-angle shots – seemingly from a helicopter or nearby buildings – so even familiar landmarks seem fresh. Each of the book’s 82 buildings is described with concise architectural commentary.

“NY Skyscrapers” provides context three ways: The volume begins with a history of skyscrapers in New York City; downtown and midtown skyscrapers are grouped, with maps; and numerous aerial group photos show the buildings’ relationship to their neighborhoods.

While any book on this subject is soon out of date, “NY Skyscrapers” includes renderings and descriptions of eight under-construction buildings scheduled to be completed by 2020.

John Hill | 303 pages | W. W. Norton & Company | 2011

A colorful and informative compendium of 200 buildings built in New York City since 2000. Overall, an exciting collection of structures, very well photographed and explained so that you understand how a building’s design evolved.

It’s intriguing to see the contrasts between this book’s author, John Hill, and AIA Guide’s Norval White and Elliot Willensky. White and Willensky are classical purists; Hill appears to be more pragmatic and concerned with technical aspects of architecture. Hearst Tower for example, “…suddenly erupt[s] Alien-like in triangular facets of glass and steel… …about as strange and abrupt as one could imagine in a single building…” according to White and Willensky. But as Hill sees it, “…the design recalls the structural inventiveness of R. Buckminster Fuller, whom [architect Norman] Foster worked with in the 1970s…” Now you’ll just have to go see the building and decide for yourself!

The book thoughtfully includes subway directions to each structure.

Jorg Brockmann, Bill Harris | 640 pages | Black Dog & Leventhal | 2002

Photographer Jorg Brockmann terms his photos “portraits,” and it’s an apt term: Like classical black and white portraits these photos reveal their subjects’ character and personality, not merely their shape and size. Frankly, I wish I had consulted this book before taking my own pictures of many of these buildings – Jorg has found just the right angle, just the right viewpoint, just the right light and just the right moment to capture his subjects.

Jorg took pains to photograph each building free of distractions such as traffic and pedestrians; the book’s designer honored that artistic commitment by placing the text in a separate section. Minimalist captions give the building’s name, location, year of construction and architect’s name.

The author, Bill Harris, has given each building one paragraph of commentary combining history and architectural critique. It’s not easy to write just a single paragraph – even if that paragraph is sometimes a quarter of a page long – when there’s usually so much to say. My hat’s off to Bill for all the research – and focus.

Andrew Alpern, Christopher S. Gray, Kenneth G. Grant | 192 pages | Princeton Architectural Press | 2015

The Dakota – and indeed NYC apartment life – is beautifully illuminated by Andrew Alpern’s new “History of the World’s Best-Known Apartment Building.” The noted architectural historian presents the most comprehensive history of The Dakota imaginable! Mr. Alpern documents the building, its builder (and family!), the architect, the neighborhood, the architectural and historical context, and even the Dakota’s residents. Fascinating reading that illuminates not only The Dakota, but also the world of apartment living in New York City.

I’m deeply honored by Mr. Alpern’s use of my photography (from the Dakota Apartments gallery) in this volume.

Mario Salvadori | 328 pages | W. W. Norton & Company; Reissue edition | 2002

Truth in advertising time: This is an old book, originally released in 1980, which explains references to Sears Tower in Chicago as the world’s tallest building, and 9 W 57th Street being called the Avon Building. But those slips of time aside, Mario Salvadori’s book is a wonderful illustrated layman’s guide to the art and science of architecture. You’ll discover secrets of the pyramids, the Eiffel Tower, the Brooklyn Bridge and many more landmarks. Mario Salvadori uses the landmarks as settings for lessons in the materials, forms and techniques of construction.

So you’ll learn not only how a Gothic arch differs from a Romanesque arch, but also why it is different, and why Gothic arches found their way into cathedrals.

Matthys Levy and Mario Salvadori | 336 pages | W. W. Norton & Company; Reissue edition | 2002

Like its prequel, “Why Buildings Stand Up,” this was written years ago. But this book has been updated to include the most (in)famous building failures – the World Trade Towers on Sept. 11, 2001.

Like “Why Buildings Stand Up,” the book uses famous landmarks to explain, in layman’s terms, the science of architecture. But in this case, the science of architectural failures, whether caused by earthquakes, storms, metal fatigue, overloading, etc.

John C. Poppeliers, S. Allen Chambers Jr. | 152 pages | John Wiley & Sons | 2003

Architects and architectural writers toss around style classifications like confetti. The “AIA Guide to New York City Architecture” lists 10 main style groups, most of which have two to four sub-types. It’s easy to get lost.

Fortunately, this slim volume describes and amply illustrates 25 architectural styles, so you can quickly tell the difference between Romanesque Revival and Gothic Revival. The one thing that I found odd is that the authors seemed to go out of their way to avoid showing any New York City-based examples of any style, even when New York has the most and best examples of that style. Oh well.

Francis D. K. Ching | 328 pages | John Wiley & Sons | 2012

What a find! “A Visual Dictionary of Architecture” is a large-format (9- by 12-inch) book profusely illustrated with black-and-white line drawings – illustrations that reveal with astonishing clarity the object, material, technique or concept being defined. The accompanying text has equal clarity and brevity. As a result, this is a “dictionary” that you’ll read cover-to-cover.

When you’ve finished, you’ll have a much better understanding of a building’s components – and probably a much richer appreciation for the work of architects.

As it happens, Francis (Frank) D. K. Ching is as prolific as he is skilled: If you like “A Visual Dictionary of Architecture,” you can go on to “Architecture: Form, Space and Order” or any of the dozen or so other volumes about architecture, interior design, construction, and technical illustration and drawing.

Carol Strickland, Ph.D. | 178 pages | Andrews McMeel Publishing | 2001

Architecture has come a long way since 10,000 B.C.E.: “The Annotated Arch” chronicles the path through time and geography, and in fewer than 200 pages! For the reader, the journey is easy: Hundreds of photos and drawings show rather than tell significant forms and styles; side-by-side comparisons make it easy to distinguish differences among styles and forms (e.g., Baroque, Romanesque, Gothic). Doctor Strickland’s text is as lively as the book’s visual presentation, enlivened by anecdotes, historical quotes and wordplay (e.g., headings such as “Escorial: The Reign in Spain,” “Going for Baroque”).

Kate Ascher | 208 pages | Penguin Books | 2011

Skyscrapers are almost synonymous with New York City: Here is a clear, layman’s explanation of what goes into a skyscraper, and why. You’ll learn all about foundations, frameworks, windows, facades, elevators, plumbing and wiring. You’ll see how an office building is different from a residential or hotel tower, and the tricks designers use to combine the three in “mixed use” buildings.

“The Heights,” like Kate Ascher’s earlier “The Works” (see below), has a simple, logical organization: Five sections – Introduction (history), Building It (design, foundations, structure, the skin, construction), Living In It (elevators, power, air, and water), Supporting It (life safety, maintenance, sustainability), and Dreaming It (the future).

Excellent diagrams, charts and photos illustrate terms and concepts; specific cases bring the theories and abstract ideas to life. And, although skyscrapers are an American invention, the book takes a world view. You’ll see how the American invention has been embraced and even improved and enlarged throughout Europe, Asia and the Middle East.

Kate Ascher | 228 pages | Penguin Books | 2005

New York City is a complex organism – composed of concrete and steel, but a living, breathing creature just the same. Under its asphalt skin, the city has arteries and capillaries to deliver electricity, water, gas and steam; a nervous system of phone and data lines; digestive tracts to remove liquid and solid waste. “The Works” explains and illustrates all of this, and more, in five chapters: Moving People, Moving Freight, Power, Communications, and Keeping It Clean. A sixth chapter, The Future, discusses challenges and possible solutions for the preceding five sections.

While the book’s subtitle “Anatomy of a City” seems generic, make no mistake: “a City” is New York City.

I found the book to be both entertaining and informative. Each topic is revealed layer-by-layer and discusses the history, planning, construction, operation, and maintenance involved. So “Streets,” for example, is a 24-page section of the Moving People chapter that includes overall stats (20,000 miles of streets and highways within the five boroughs) and history (the Commissioners’ Plan of 1811 established Manhattan’s Grid Plan), then moves on to regional traffic planning, monitoring, and signaling, street construction and maintenance, parking, signage – even trees.

John Tauranac | 176 pages | Tauranac Maps | 2008

The concept of “Manhattan Block By Block” is simple and logical: Slice the island into 15 strips, south to north; then dice each strip into two to four maps, west to east – for a total of 47 two-page maps. The map scale is large enough to show the names of individual buildings and landmarks, but the total package is small enough to be portable: it will fit (snugly) into a number 10 business envelope.

Neighborhoods are color-coded, typefaces are very legible, icons are (mostly) easy to follow. Street-level detail includes subway and bus routes, and traffic flow. (Subway and bus routes change, so those details are helpful but not totally reliable.)

Street and subject indexes both use combination page and map coordinates, so it’s a snap to locate landmarks this way. Visitors should read (and even New Yorkers will enjoy and learn from) the introductory section, which explains Manhattan’s layout, house numbering, neighborhoods, transit and more.

Note: This was out of stock at Amazon at this writing, but is worth tracking down at bookstores.

Patrick Bunyan | 417 pages | Empire State Editions | 2011

New York City is, of course, much more than buildings and geography: It is also the people and events within its facades and borders. While there are scores, if not hundreds of New York City history books, “All Around The Town” stands out by being an historical atlas, organized by Manhattan neighborhood and street rather than by chronology. The people and events are revealed in fast-moving snippets, rather than in essays. A sample:

172 Bleecker Street * Author, playwright and critic James Agee lived on the top floor of this building from 1941 to 1951. It was here that he wrote the screenplay for The African Queen.

Although there are hundreds of thousands of buildings in New York City, designed over the course of 400 years by thousands of architects, there are relatively few architectural style categories. The “AIA Guide to New York City” lists just 10 style categories, including “The Picturesque,” which in turn includes the sub-categories Romanesque Revival, Stick, Shingle, and Queen Anne.

Romanesque Revival, according to AIA Guide, is more common in Chicago. It is based on medieval bold arch and vault construction. (You may also see this style referred to as Rundbogenstil or Round Arch Style.)

Stick style makes its wood skeleton visible, as in half-timbered construction.

Queen Anne style is marked by strong vertical emphasis (tall windows, high-peaked roofs, etc.) and elaborate ornamentation. Queen Anne style buildings frequently include turrets.

Shingle style grew out of Queen Anne style, using wood shingles as its protective/decorative veneer. Originated in New England.

AIA Guide: p. xii.

John C. Poppeliers, S. Allen Chambers Jr. | 152 pages | John Wiley & Sons | 2003

Architects and architectural writers toss around style classifications like confetti. The “AIA Guide to New York City Architecture” lists 10 main style groups, most of which have two to four sub-types. It’s easy to get lost.

Fortunately, this slim volume describes and amply illustrates 25 architectural styles, so you can quickly tell the difference between Romanesque Revival and Gothic Revival. The one thing that I found odd is that the authors seemed to go out of their way to avoid showing any New York City-based examples of any style, even when New York has the most and best examples of that style. Oh well.

New York City has nearly a million buildings, erected over a span of four centuries in a bewildering (and fascinating) palette of styles. Yet most New Yorkers and visitors are oblivious to the city’s architectural riches. That’s not a criticism – just the observation that New York is so fast-paced, people rarely have a spare moment to appreciate the art and science of our built environment.

Here’s another observation: New York City has hundreds of museums of every description. But the Big Apple could be considered a museum itself: A 301-square-mile museum of architecture, where the exhibits change daily and reflect 400 years of development. Our homes, buildings, bridges, tunnels, subways and parks are fascinating works, accessible to all. Take the time to look around – and up and down – and you’ll discover a mosaic of history, art, and science in every borough.

If you are a New Yorker, you probably live or work just a short walk from some architectural treasure – possibly just minutes from an historic district filled with landmarks. If you’re a visitor, then your hotel is probably close to a landmark, or may itself be historic. To enjoy this wealth, all you need are your feet and your eyes. Camera is optional but recommended. As noted above, the exhibits change daily – your favorite building or park could be changed or demolished tomorrow, so capture it today. You can collect buildings, the way bird-watchers collect species.

This site is the start of what I hope will be a layman’s guide to and sampler of New York architecture: The photo galleries and related articles are meant to entice. As a layman’s guide, NewYorkitecture.com is not heavy on architectural jargon, but the site will be developing a modest beginner’s course on architectural appreciation. You won’t exactly learn architecture, but you’ll learn the differences between a column and a pilaster, and how to distinguish Gothic from Romanesque. At this writing, of course, the site is limited. I’ll be adding to it every week, so it will probably be worth your while to come back every week.

The navigation at the top of the screen is the most obvious way to get around – categorized to make it easier to follow. The home screen photos are linked to the ten most recent image galleries – just click to visit. You can also use the previous/next links in each gallery to explore another subject.

I include parks in this site because they are all designed – what I call “Parkitecture” – not just undeveloped land.

Enjoy the photo galleries! When you open a gallery, the slide show starts automatically. Click the icon next to “full screen” for a more dramatic view; click Play button in the bottom left corner to resume the slideshow. If you prefer, you can also use your keyboard left-arrow and right-arrow keys to go back and forth. When you’re in full-screen mode, the up and down arrows control the caption and carousel ribbon at the bottom of the screen. Press the [Esc] key to exit full-screen mode.

So jump in, explore, have fun. Then put on your most comfortable walking shoes and meet New York’s fabulous architecture in person!

If you are an out-of-town visitor to New York City, welcome! Take a look at the Guides section for helpful info.

If you find that the architecture bug has bitten you – beware, there is no antidote – you will need a better guide. The best guide, IMHO, is “ AIA Guide To New York City ” by Norval White and Elliot Willensky with Fran Leadon. (Oxford University Press, New York.) The 1,055-page fifth edition includes 955 pages of maps, photos and detailed block-by-block, building-by-building commentary on virtually every architecturally significant structure within the five boroughs. The book even notes significant demolitions! There are subject and address indexes, a glossary of architectural terms, even touring and photography tips. You can use the book as a walking tour guide, as a reference book, or as a history book of sorts (read about real estate development battles, zoning law trades, etc.). The authors’ scholarship is matched by their wit, so you’ll be entertained as well as educated. The “AIA” in the title, by the way, stands for American Institute of Architects.

Suggested Reading: NewYorkitecture.com is intended as a recreational site – exploring New York City’s architecture just for the fun of it. If you want to dig deeper, here’s a page of excellent research sites: Web Resources. If you’d rather learn from books you can hold, here’s a short list of excellent references: Favorite Books.

When I found myself with time on my hands, I resumed an old interest – photography. That led to going around town snapping pictures of places I knew as a kid (we moved around a lot), and that rekindled a fascination with architecture. Architecture fills one of our most basic needs – shelter – with beauty, utility and economy. Every building is a unique expression of that art and science, and many are wonders to behold. Within a month I realized that I just had to share my finds with others.

But, truth be told, I’m not an expert on architecture: I’m a gourmand, not a gourmet in this respect.

Tech notes: I’ve used six cameras in preparation of this site: Canon G5, Canon SX110 IS, OlympusSZ-10, Canon SX40, Canon Rebel T3i, and Canon 5D mark iii. The Canon 5D optics, speed and tech features leave the others in the dust – but is incredibly heavy. I’m now lugging 20 pounds of gear. But I miss the SX40, for its extreme zoom range of 24mm-840mm (35mm equivalent). That let me shoot whole facades from close in, or zoom in on a 20th-story gargoyle without carrying and changing lenses. Many galleries include High Dynamic Range (HDR) images – photos that merge three exposures to gain greater highlight and shadow detail. In these images, you may see ghost images of people and vehicles that moved between exposures. This is intentional. I also use Adobe’s Lightroom instead of HDR to improve the photos. In addition to saving more shadow and highlight detail, Lightroom lets me correct perspective (keeps verticals vertical).

NewYorkitecture.com does not collect any personal information. Links in NewYorkitecture.com may identify this site as the traffic source, but will not identify you as an individual. (Of course if you jump to a site where you have an account – say Amazon.com – that site will probably recognize you as a returning visitor.)

NewYorkitecture.com participates in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to amazon.com.

NewYorkitecture.com exercises reasonable care in linking to other sites, but cannot be responsible for the content of other sites.

Except where noted otherwise, all photography and writing is my own. You are welcome to enjoy and quote text from NewYorkitecture.com; credit would be appreciated.

I’ve invested a great deal of time and energy in creating these photos. I’m quite happy to share my discoveries with you in this site – and without ads! But I do ask that you respect my copyright and not re-use my photos without permission. Thank you!

You may order photos – digital or prints – on the Buy Photos page.

Digital photography is wonderfully fast and cheap compared to conventional film photography: There’s no film to buy (or run out of!) or process – a single memory chip can store more than a thousand images, and be reused indefinitely. But digital photo display can be challenging, because digital photos don’t capture and store all of the image the same way that the human eye sees it. Frequently, what we see on the screen lacks shadow details or highlight details or both. And cameras are easily tricked by unusual lighting conditions, such as scenes with strong backlighting.

Architectural photography typically includes strong backlighting – a building with sky as backdrop – and/or shooting in bright sun, where shadows are especially deep and dark compared to the rest of the photo. Consequently, a typical building photo will have some areas that are underexposed and/or some areas that are overexposed. You won’t be able to see (on the computer screen) the details in shadows or highlights that the eye would normally see in real life.

When I started taking photos for this website I had to discard many photos because the camera meter was tricked by the backlighting. Then I started bracketing photos – taking shots that were intentionally overexposed and underexposed. The best of the three exposures would make it to the website. This was better, but still lacking.

In January, 2013 I began using High Dynamic Range (HDR) photography for NewYorkitecture.com. I was still bracketing each shot. But instead of selecting one of three images I used software to combine all three images. The normal exposure provided the photo’s midtones; the underexposed image provided the highlight details; the overexposed shot contributed the shadow details.

This technique imposes its own set of challenges: To work, the three images have to be EXACTLY the same. If the camera shifts even a fraction of an inch the final result won’t be sharp. And anything that moves between images – like cars, pedestrians, birds or planes – will be blurred or “ghosted” in the final image. So every shot has to be taken on a heavy tripod, and usually multiple times to catch breaks in traffic. But the results were often worth the extra hassles.

The software that I use can also create special effects with those three images – I’ve included a couple in the gallery above – but I only use the default “natural” setting for the galleries in this site.

If you’re interested in using this technique yourself, you’ll need: A good tripod; a camera that lets you over/under expose (preferably with an automatic bracketing mode); software to combine the images. I’ve tried a few different software packages, I like Photomatix from hdrsoft.com. They have a $39 “Essentials” version (free trial), and a $100 “Pro” version that has added features – the most important being the ability to automatically batch process hundreds of images.

In late April, 2013 I started using Adobe Photoshop Lightroom 4 to make additional improvements – the most important being perspective correction. When you point a camera upwards to capture a whole building, vertical lines converge toward the top; the building seems to lean backwards. Occasionally, this makes a dramatic photo, but as a steady diet…. Lightroom (or Adobe Photoshop) can correct this, bringing all verticals back to vertical. The program also gives me greater exposure control than I have with HDR alone, so I can bring out even more detail. Many of Lightroom’s features are available in the free Gimp program, but Lightroom’s interface is so much easier to use.

I’ve stopped using HDR as a regular practice. I’m now using Lightroom and Photoshop to tweak exposures most of the time, saving HDR for only the most challenging lighting conditions.

GIMP – The GNU Image Manipulation Program is available at: www.gimp.org/. Adobe now “sells” Lightroom and Photoshop together as a Creative Cloud bundle for photographers, at $9.99 per month. This may seem odd, if you’re used to buying software, but in practice it’s far more economical than the old purchase-and-annual-upgrade cycle. As a bonus, you always have the most powerful, up-to-date software. You can get the details at Adobe.com.

This gallery is just for fun – posterized versions of images used elsewhere in this site. These images all started out normally – sets of bracketed exposures. Then I used Photomatix software to apply color shifts and luminosity effects with the “Grunge” preset. (See NewYorkitecture.com Photography Technique for more information about this technique.)

The images in the gallery are of buildings in the Chelsea, Soho, Ladies Mile, Civic Center, Astor Plaza and Flatiron districts.

Whoever said it first said it right: Windows are the eyes of the building. What’s more, it’s true whether you’re standing inside or outside.

From the outside, windows reveal a building’s purpose, character and personality. In many cases you can even predict the mood of its occupants. From the inside, windows shape the view and invite – or exclude – the sun. “When you are designing a window,” said Finnish architect Alvar Aalto, “imagine your girlfriend sitting inside looking out.” (From the book “100 Ideas that Changed Architecture” by Richard Weston.)

Windows were even considered an indication of wealth: England’s King William III had a “window tax” (derided as “daylight robbery”) that was a royal attempt at a progressive property tax. The more windows in your house, the more tax you paid.

Philosophical and political points aside, what started out as a rough hole covered by animal hide has become one of the most important aspects of a building’s architectural style, as well as a component of the architectural system. New York is blessed with examples of dozens of traditional and modern window types and styles. Some people have even made a hobby of “collecting” windows, photographically – just search Pinterest.com, Flickr.com, or Picassaweb.google.com for fun!

Windows in the classical Greek style had formal embellishments: pediments, architraves, and cornices. Both Greek (post-and-lintel) and Romanesque (round arch) styles often grew columns or pilasters. Gothic (pointed arch) styles could become quite complex, with arches wrapped in more arches, sometimes combined with circular windows.

The earliest windows were casement windows: the moving frame swung out to permit ventilation. Sliding sash windows are a more recent development. Stationary windows are a byproduct of air conditioning.

The size and shape of windows were limited by engineering considerations. A building’s exterior wall was a structural element – too many windows and the building falls down! But as iron, steel and concrete replaced brick and stone, these stronger structural materials allowed bigger windows. Finally, frame construction shifted all of the structural load from the wall to systems of columns. This gave us “ribbon windows” (one Le Corbusier’s “Five Points of a New Architecture”) and all-glass curtain walls.

Although modern windows are simpler visually – pilasters and pediments are quite unlikely – they have become complex from a manufacturing standpoint. Glass is a poor insulator, and in an energy-conscious world designers have created window systems of two or even three plates of glass locked in a sealed frame. The glass may be tinted or coated to reduce transmission of infrared rays – or for aesthetic effects.

Here’s a modest captioned photo gallery of interesting windows I’ve collected around New York – see if they don’t make you look at (and though) windows in a new way. Windex is optional.

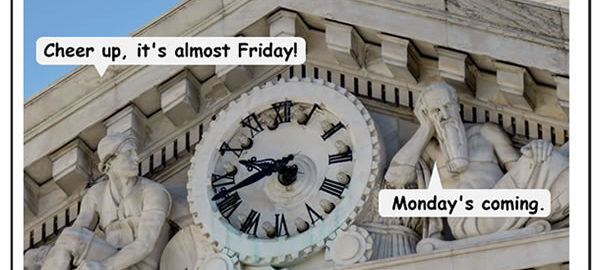

New York’s architecture is richly adorned with terra cotta figures – realistic and fanciful – with expressions that are forever frozen. Some are deeply symbolic, some are merely decorative, and some are decidedly the architect having some fun.

I decided to have a little more fun by giving these characters voices. Stay tuned – more to come.

You must be logged in to post a comment.