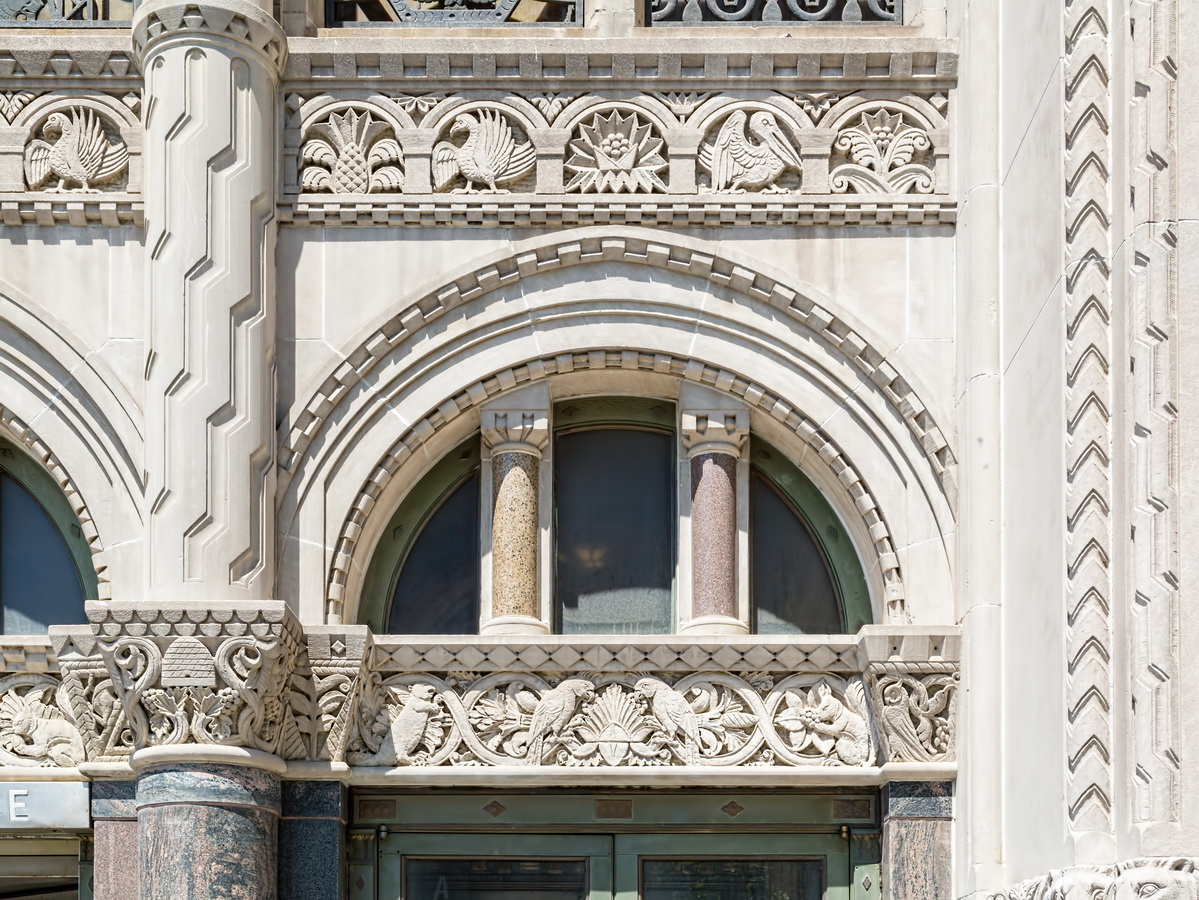

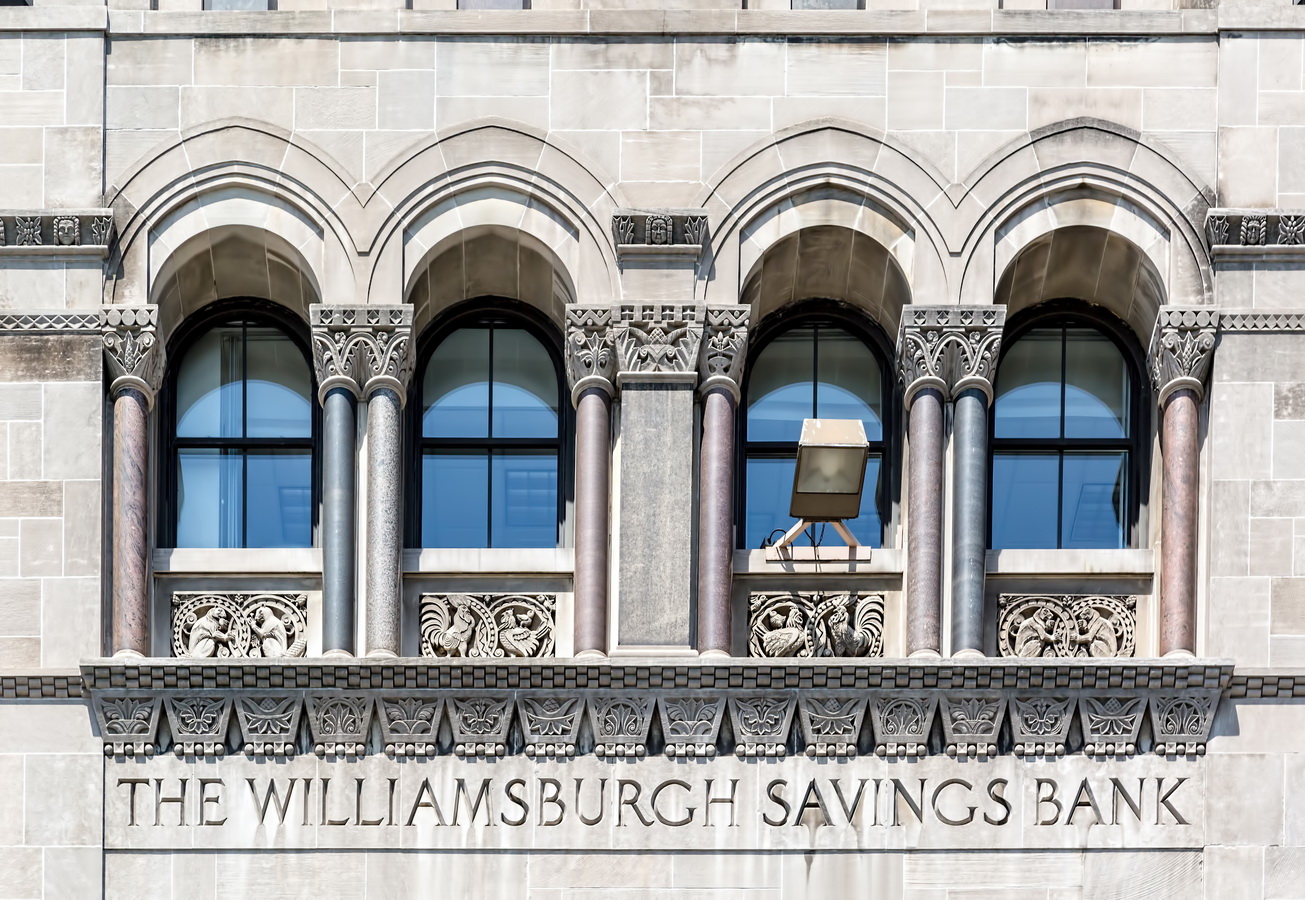

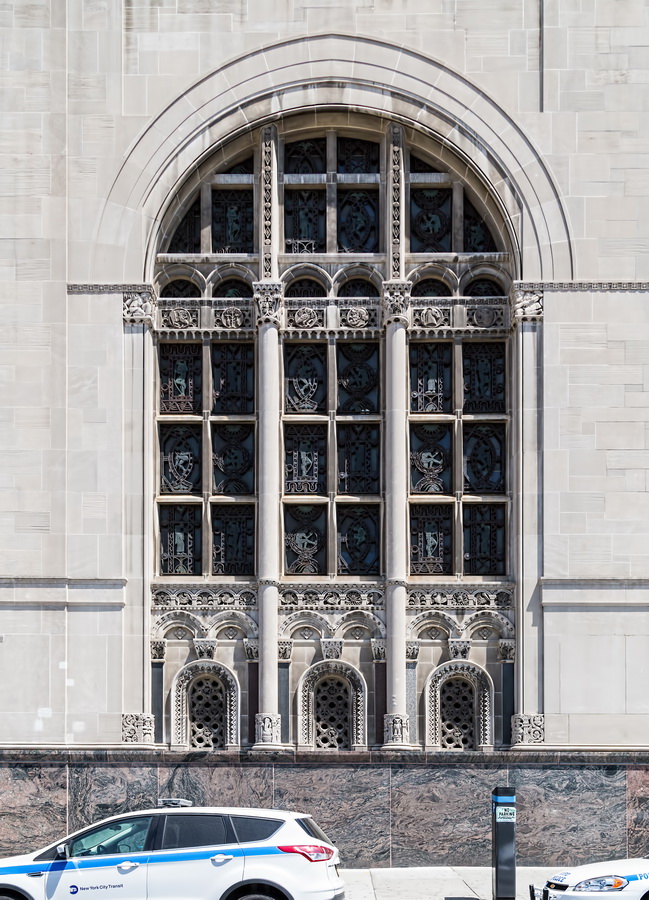

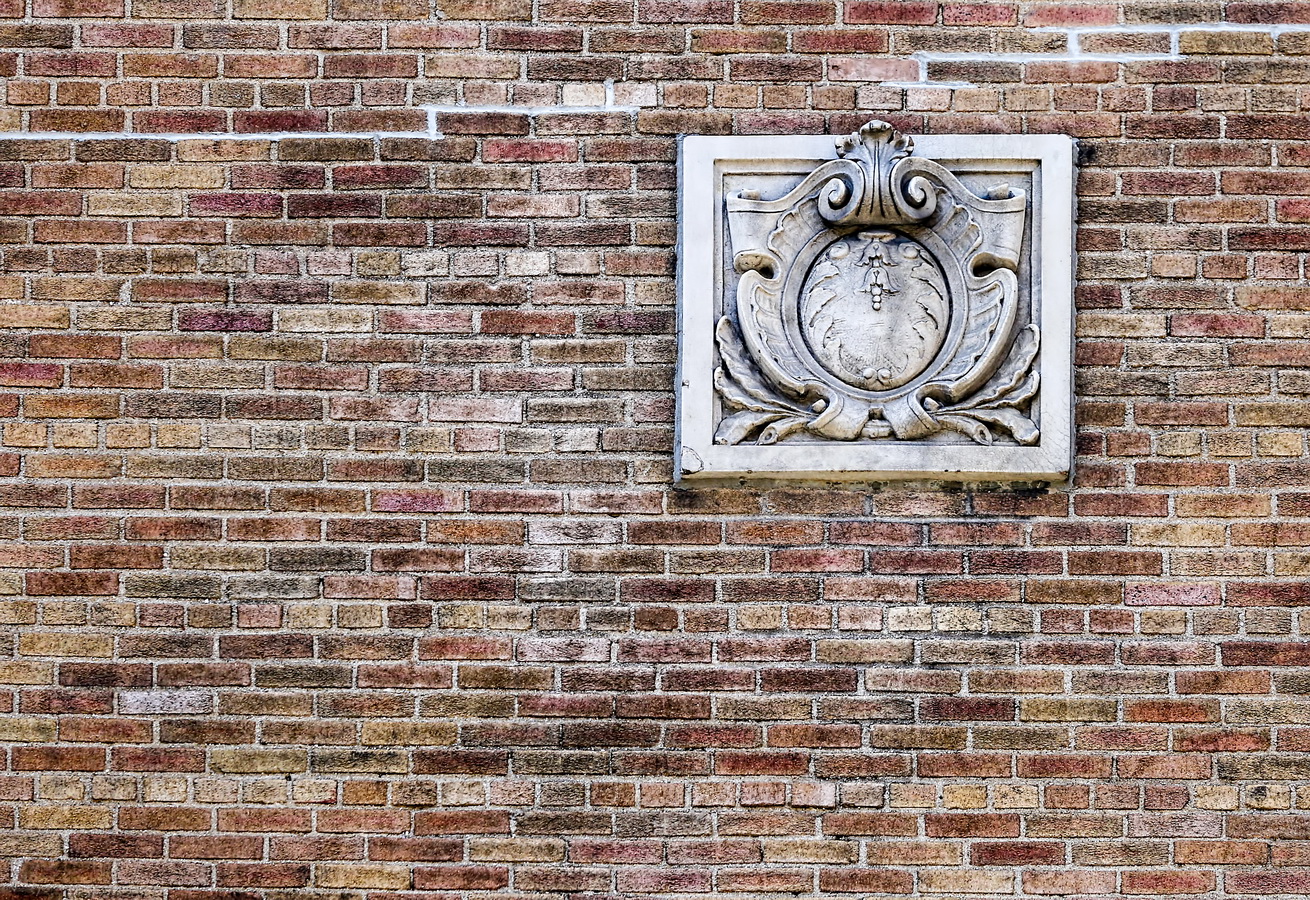

Williamsburgh Savings Bank is New York architecture that entertains from afar – and from close up. The tower’s graceful taper dominates the Brooklyn skyline for miles; the Rene Chambellan sculpture around the base fascinates passers-by. More sculpture, mosaics, and majestic vaulted ceilings overwhelm visitors inside.

The landmark fulfills architect Robert Helmer’s wish that the tower “be regarded as a cathedral dedicated to the furtherance of thrift and prosperity of the community it serves.” Not bad for a tiny bank that started out in the basement of a (now-demolished) church in 1851, before Williamsburgh dropped the “h” from its name.

Architects Halsey, McCormack & Helmer specialized in banks, so it is a little ironic that one of the firm’s non-bank buildings was the Central Methodist Episcopal Church – right next door to their “cathedral of thrift.”

The building is based on a steel “portal frame” – a special structure designed to support the weight of the massive tower above the equally massive void of the banking hall. (Think of this as a 35-story office building on top of a six-story church.) The bank insisted – over the architects’ objections – on a gilded dome as a crown for the tower. The dome was an architectural reference to Williamsburgh Savings Bank’s original headquarters in downtown Williamsburg.

When built, this was the tallest building in Brooklyn, and the clock was the largest four-sided clock tower in the world. “Brooklyn’s wristwatch” sometimes had trouble keeping time, but it seems to have been fixed. Although this was its headquarters, Williamsburgh Savings Bank only used two floors (above the banking level) as offices. The rest of the tower was rented – and for some reason, mostly to dentists!

Williamsburgh Savings Bank was acquired by Republic National Bank, and then merged into HSBC. In 2005, a partnership of the Dermot Company and Canyon-Johnson Urban Funds bought the tower. The lower floors were converted to Skylight One Hanson – event space – while the upper floors became 1 Hanson Place luxury condominiums.

The tower has the distinction of being triple-designated by the NYC Landmarks Preservation Commission: as an individual landmark (1977), as part of an historic district (1978), and as an interior landmark (1996).

Urban Omnibus has an exceptional narrative on the building’s history.

Williamsburgh Savings Bank Vital Statistics

- Location: 1 Hanson Place at Ashland Place

- Year completed: 1929

- Architect: Halsey, McCormack & Helmer

- Floors: 41

- Style: neo-Romanesque

- New York City Landmark: 1977, 1978 (Brooklyn Academy of Music HD), 1996 (interior)

Williamsburgh Savings Bank Recommended Reading

- Wikipedia entry

- NYC Landmarks Preservation Commission designation report

- NYC Landmarks Preservation Commission designation report (interior)

- NYC Landmarks Preservation Commission designation report (Brooklyn Academy of Music Historic District)

- The New York Times STREETSCAPES: Williamsburgh Savings Bank; Resolving the Case of Missing Muntins (November 12, 1989)

- The New York Times For Brooklyn’s Beacon, the Luxe Life (June 11, 2006)

- NY Landmarks Conservancy: Tourist In Your Own Town # 6 – Williamsburgh Savings Bank Tower

- Urban Omnibus: From the Archives: The Williamsburgh Savings Bank Tower

- Forgotten New York blog

- City Realty review

- Emporis database