Graham Court is sometimes called “Harlem’s Dakota,” but it’s actually much closer in style to the 1908 Apthorp Apartments, on Broadway at W 78th Street.

The building’s grandeur stems from its sponsor: Graham Court was commissioned by William Waldorf Astor, and designed by the firm of Clinton & Russell. Before joining the firm, Charles Clinton was the architect of the Park Avenue Armory, Manhattan Apartments and New York Athletic Club, among others. With William Russell, the firm went on to design the Apthorp Apartments, Langham Apartments, and Astor Apartments (and a score of important commercial buildings).

The last 50 years have been hard on Graham Court: Successive owners haven’t been as quality-conscious as the original builders. One commentator after another (see Recommended Reading list) has lamented the security problems, disrepair, and financial problems of the landmark.

But beyond the unfriendly iron front gates and crudely hand-painted “No Parking” sign at the service entrance, Graham Court is still mighty impressive. I hope I look as good when I’m 113!

Graham Court Vital Statistics

- Location: 1925 Adam Clayton Powell Jr. Blvd. at W 116th Street

- Year completed: 1901

- Architect: Clinton & Russell

- Floors: 8

- Style: Italian Renaissance

- New York City Landmark: 1984

Graham Court Recommended Reading

- Wikipedia entry

- NYC Landmarks Preservation Commission designation report

- The New York Times Streetscapes | Commissioned by Astor | Buildings for a City He Could Live Without (May 28, 2009)

- The New York Times Streetscapes: Graham Court; Grande Dame Tries to Regain Her Respectability in Harlem (July 12, 1987)

- The New York Times NEIGHBORHOOD REPORT: HARLEM; When Renovation Erases the Past (April 3, 1994)

- New York Sun Once-Heralded Address Lags Behind Rest of Harlem (January 19, 2006)

- New York Daily News Longtime residents of iconic Harlem building remember prize that got away (April 28, 2011)

- Ephemeral New York blog

- My Life In Gardens blog

- Luxury Apartment Houses of Manhattan: An Illustrated History (Dover Architecture)

- New York’s Fabulous Luxury Apartments: With Original Floor Plans from the Dakota, River House, Olympic Tower and Other Great Buildings

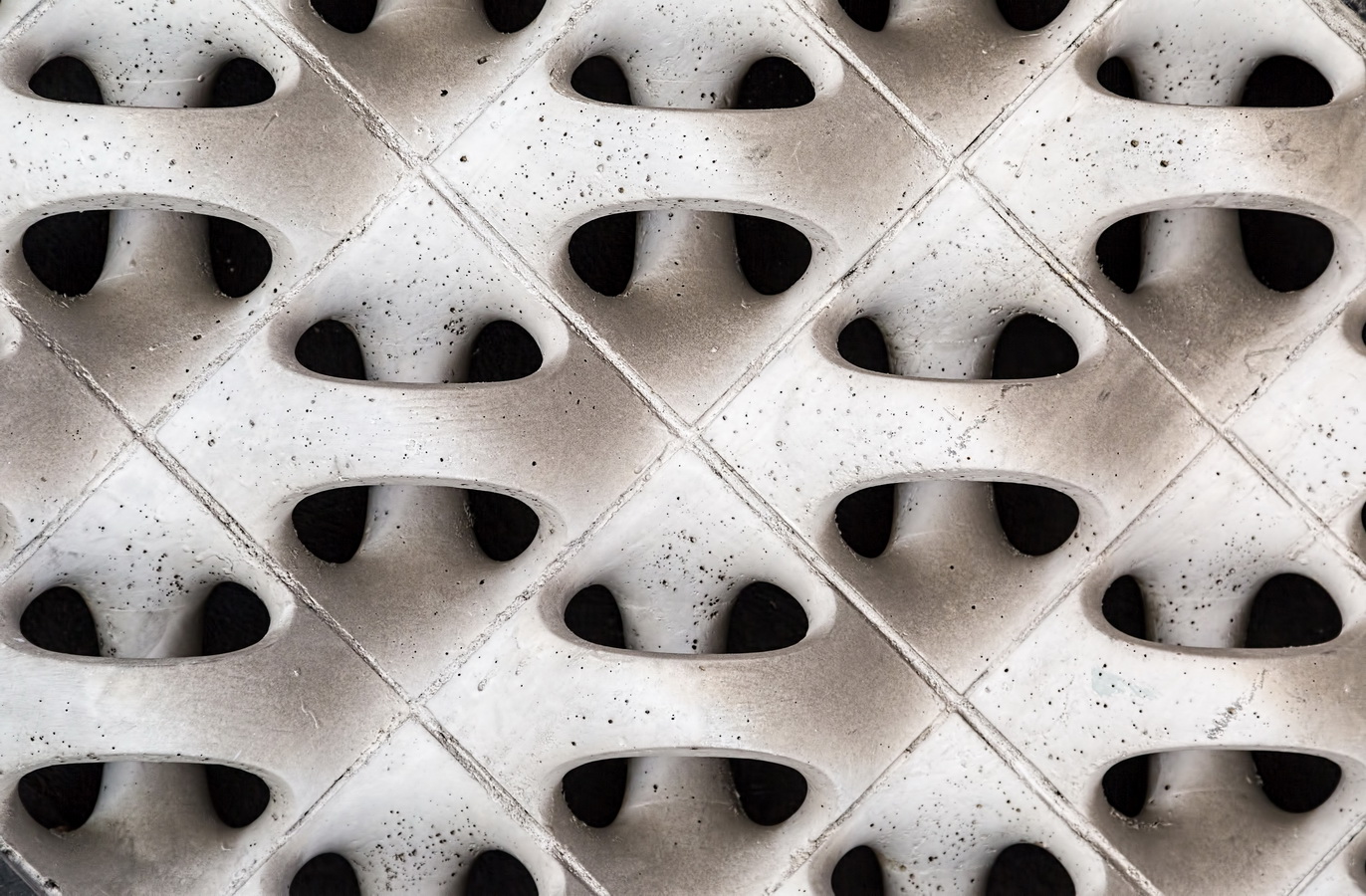

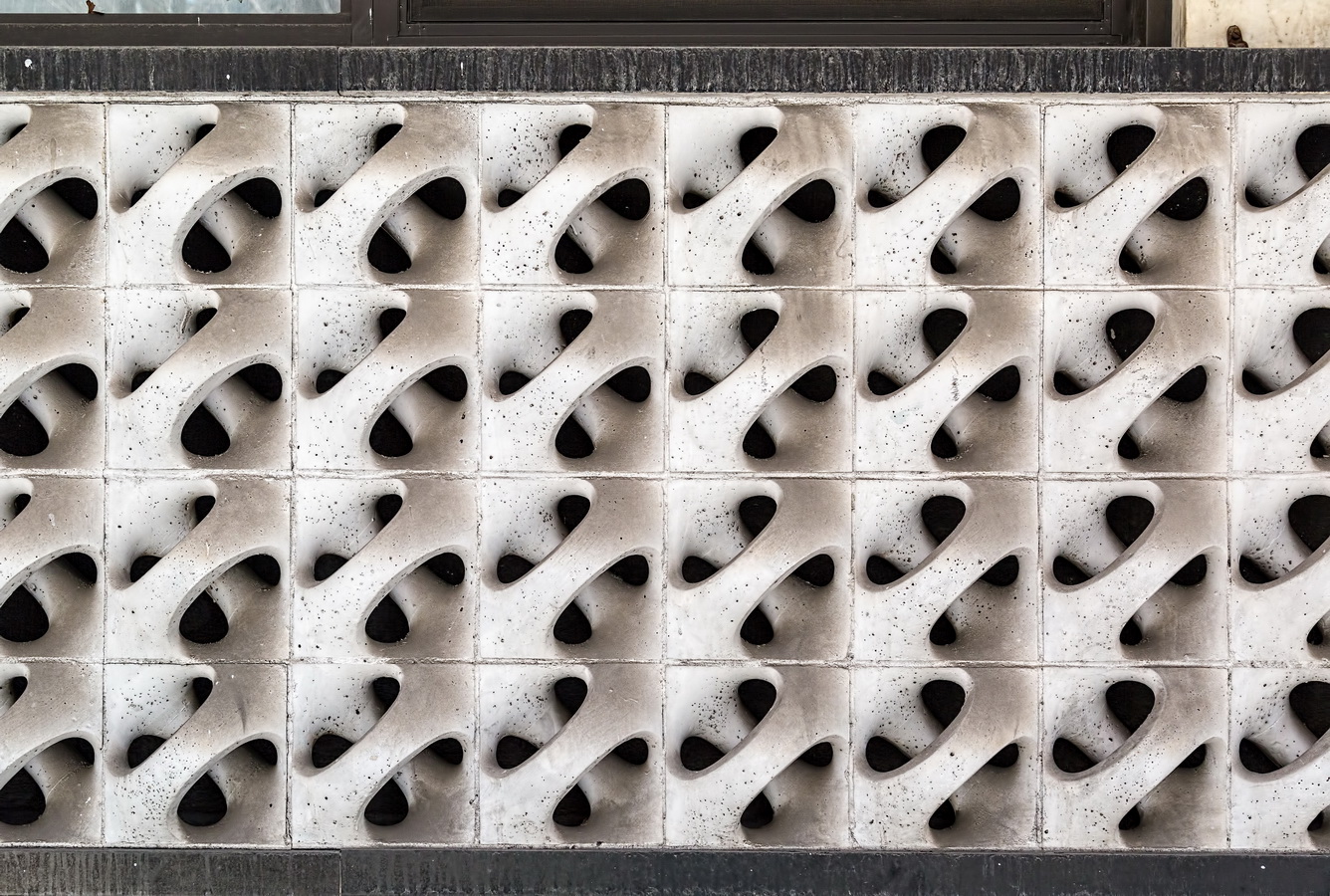

![Entry detail: Prada store [2] Entry detail: Prada store [2]](https://www.newyorkitecture.com/wp-content/gallery/random-may-2014/NO5A8638_resize.jpg)

![Entry detail: Prada store [1] Entry detail: Prada store [1]](https://www.newyorkitecture.com/wp-content/gallery/random-may-2014/NO5A8640_resize.jpg)

![Entry detail: Prada store [3] Entry detail: Prada store [3]](https://www.newyorkitecture.com/wp-content/gallery/random-may-2014/NO5A8646_resize.jpg)

![Entry detail: Prada store [4] Entry detail: Prada store [4]](https://www.newyorkitecture.com/wp-content/gallery/random-may-2014/NO5A8648_resize.jpg)

![Entry detail: Prada store [5] Entry detail: Prada store [5]](https://www.newyorkitecture.com/wp-content/gallery/random-may-2014/NO5A8649_resize.jpg)