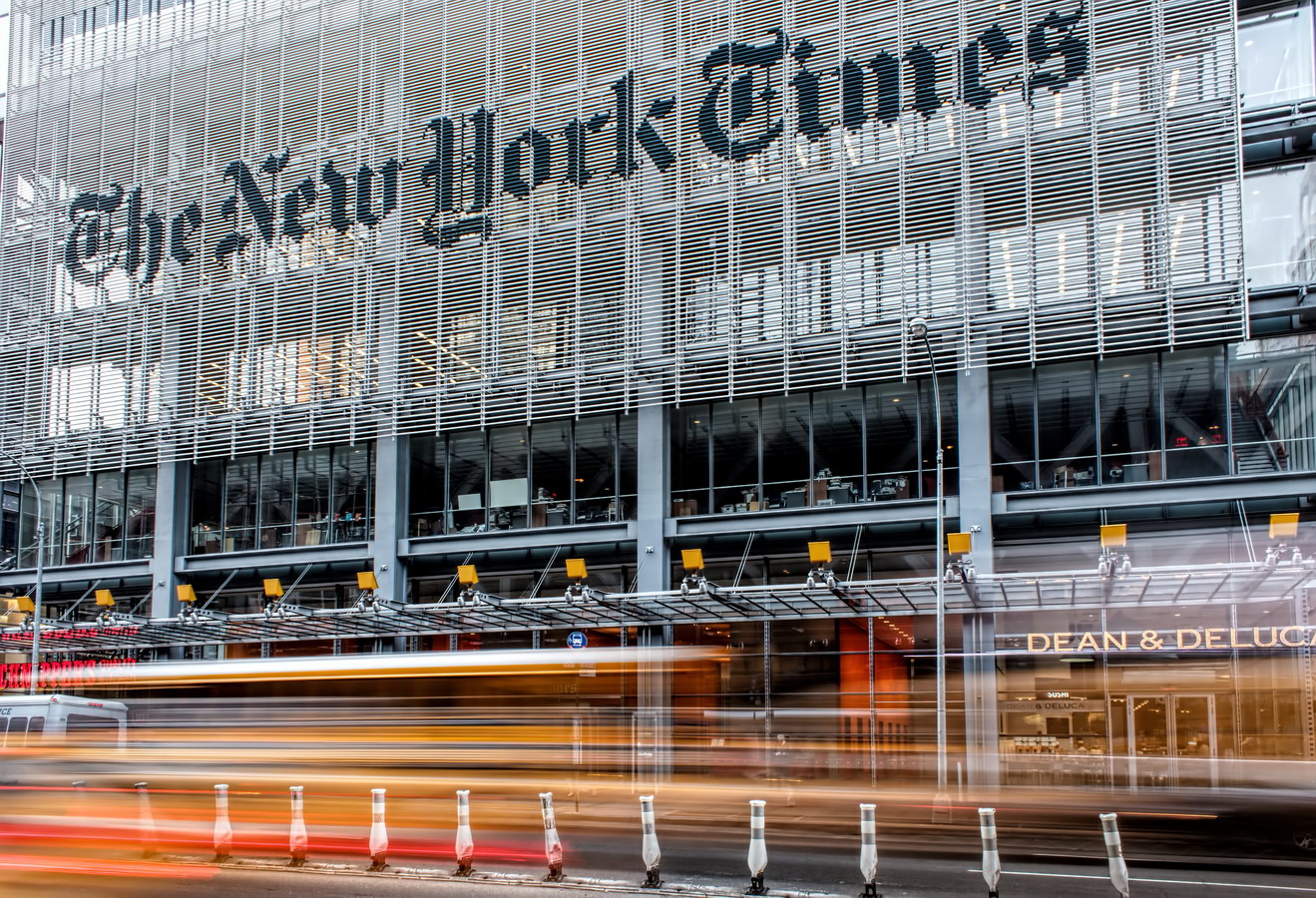

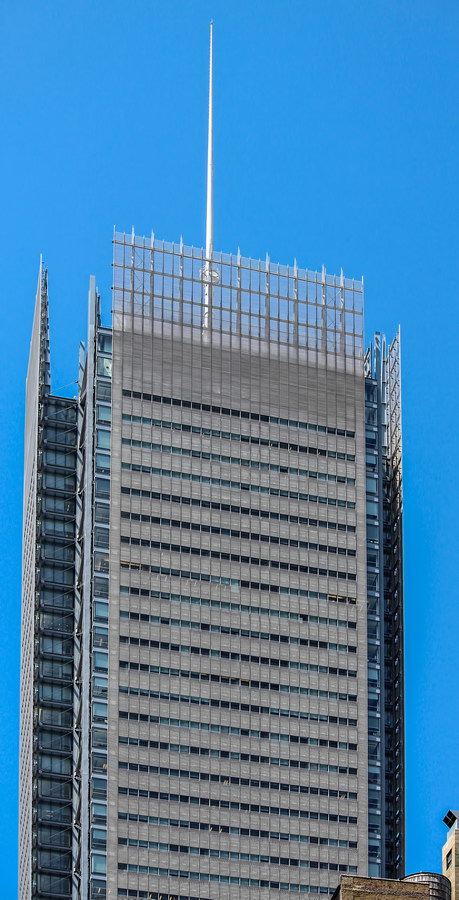

New York Times Building, called the ugliest building in New York City by the American Institute of Architects, is nonetheless impressive in many ways. The exposed frame, ceramic-rod screen, monumental logo and sheer height make it stand out even in a neighborhood filled with buildings that scream for attention.

(Some critics say it was crazy for the Times to spend nearly half a billion dollars for a new headquarters (58% ownership of the $850 million cost) while the paper’s fortunes are shrinking – but that’s neither an architectural nor an aesthetic argument.)

The New York Times Building’s innovative ceramic rod screen – which dramatically cuts energy costs by blocking solar heat – became an embarrassment: Four climbers (so far) have used the screen as a ladder to scale the 52-story facade. The first climber said he did it to protest global warming: Ironic, as his action discourages use of this technology to cut greenhouse gas emissions.

The high-tech lobby, meanwhile, revives and updates an old newspaper tradition: the news is on display for passers-by.

New York Times Building Vital Statistics

- Location: 620 Eighth Avenue between W 40th and W 41st Streets

- Year completed: 2007

- Architect: Renzo Piano Building Workshop and FXFOWLE Architects

- Floors: 52

- Style: postmodern

New York Times Building Recommended Reading

- Wikipedia entry

- The New York Times Architecture Review – Pride and Nostalgia Mix in The Times’s New Home (November 20, 2007)

- Architectural Record: The New York Times Building

- The New York Times Building website

- Arch Daily: The New York Times Building Lobby Garden (January 10, 2011)

- The Architects Newspaper: Climbing the Times (June 6, 2008)

- The City Review Plots & Plans

- Modern Steel: Inside Out (January, 2009)

- Gawker: Is This the Ugliest Building in New York? (July 6, 2010)

- NY Daily News Top 10 ugliest buildings in New York City (July 5, 2010)

- Web Urbanist: Floors So Vain: The World’s Ten Tallest Vanity Heights (September 29, 2013)

![Lipstick Building [9] Lipstick Building [9]](https://www.newyorkitecture.com/wp-content/gallery/lipstick-building/IMG_3697_resize.jpg)

![Lipstick Building [17] Lipstick Building [17]](https://www.newyorkitecture.com/wp-content/gallery/lipstick-building/IMG_4153_resize.jpg)

![Lipstick Building [16] Lipstick Building [16]](https://www.newyorkitecture.com/wp-content/gallery/lipstick-building/IMG_4054_resize.jpg)

![Lipstick Building [15] Lipstick Building [15]](https://www.newyorkitecture.com/wp-content/gallery/lipstick-building/IMG_4006_resize.jpg)

![Lipstick Building [14] Lipstick Building [14]](https://www.newyorkitecture.com/wp-content/gallery/lipstick-building/IMG_4002_resize.jpg)

![Lipstick Building [13] Lipstick Building [13]](https://www.newyorkitecture.com/wp-content/gallery/lipstick-building/IMG_4000_resize.jpg)

![Lipstick Building [12] Lipstick Building [12]](https://www.newyorkitecture.com/wp-content/gallery/lipstick-building/IMG_3998_resize.jpg)

![Lipstick Building [11] Lipstick Building [11]](https://www.newyorkitecture.com/wp-content/gallery/lipstick-building/IMG_3995_resize.jpg)

![Lipstick Building [10] Lipstick Building [10]](https://www.newyorkitecture.com/wp-content/gallery/lipstick-building/IMG_3703_resize.jpg)

![Lipstick Building [1] Lipstick Building [1]](https://www.newyorkitecture.com/wp-content/gallery/lipstick-building/IMG_3645_resize.jpg)

![Lipstick Building [8] Lipstick Building [8]](https://www.newyorkitecture.com/wp-content/gallery/lipstick-building/IMG_3684_resize.jpg)

![Lipstick Building [7] Lipstick Building [7]](https://www.newyorkitecture.com/wp-content/gallery/lipstick-building/IMG_3680_resize.jpg)

![Lipstick Building [6] Lipstick Building [6]](https://www.newyorkitecture.com/wp-content/gallery/lipstick-building/IMG_3667_resize.jpg)

![Lipstick Building [5] Lipstick Building [5]](https://www.newyorkitecture.com/wp-content/gallery/lipstick-building/IMG_3666_resize.jpg)

![Lipstick Building [4] Lipstick Building [4]](https://www.newyorkitecture.com/wp-content/gallery/lipstick-building/IMG_3658_resize.jpg)

![Lipstick Building [3] Lipstick Building [3]](https://www.newyorkitecture.com/wp-content/gallery/lipstick-building/IMG_3655_resize.jpg)

![Lipstick Building [2] Lipstick Building [2]](https://www.newyorkitecture.com/wp-content/gallery/lipstick-building/IMG_3650_resize.jpg)